A really terrifying story never leaves you. It lurks within the long evening shadows, calls out within the night through mysterious tremors, and blows down your neck if you feel a sudden chill. With Halloween approaching, we asked six of our academic experts to inform us concerning the scariest book they've ever read. From haunted houses to murderous beasts and nefarious vampires, these are terrifying reads that can linger in your mind long after you've turned the last page.

Dictionary of Monsters and Mysterious Beasts by Carey Miller (1974)

Nick Freeman, CC BY

– says Lady Macbeth is “The Eye of Childhood / That Fears the Painted Devil.” She is correct. I purchased Dictionary of Monsters and Mysterious Beasts at a faculty book fair once I was seven. I used to be intrigued by the menacing goblin on the duvet (who looked like my science teacher) and the duvet's promise of creatures “beautiful and hideous, fascinating and terrifying” (one other Macbeth allusion, though I didn't comprehend it).

I reveled within the strangeness of the amphisbania (two-headed reptiles that eat ants), basilisk (which hatched from cockerel eggs and was breathtaking) and manticore (which one way or the other combined the face of a person, the body of a lion, and the tail of a scorpion). But nothing prepared me for page 172. Mary French's werewolf drawing gave me nightmares.

But I kept an eye fixed on it until I progressively moved on to a stronger offering: anthologies of classic Gothic stories edited by Peter Haining and with the arrival of adolescence, thrillingly brutal horrors James Herbert AND Guy N. Smith. Miller's book was undoubtedly a milestone in the event of my literary interests. I don't go anywhere without silver bullets.

The review was written by Nick Freeman, a reader of late Victorian literature

Flypaper by Elizabeth Taylor (1969)

They eat, CC BY-SA

“Scary” is simply too mild a word to explain the writer's terrifyingly believable conclusion Elizabeth Taylor story “The Flypaper”. It begins with 11-year-old Sylwia, unloved and unloved, riding a bus to a hated music lesson on the grey outskirts of a provincial town.

When a person starts harassing her, she is calmed down by a middle-aged woman who she believes is “keeping an eye on the situation.” It is that this lady who involves the rescue when the person follows Sylwia from the bus, taking her home.

The shocking solution presents a table set for 3 people and the titular flypaper: “Some flies were still half-dead and were hopelessly trying to free themselves. But they were caught forever.” Roald Dahl adapted this story into his collection, Tales of the unexpected in 1979, saying: “This is so neat and nice and creepy that I wish I had thought of it myself.”

This review was written by Colette Paul, senior lecturer in creative writing

Dracula by Bram Stoker (1897)

WikiCommons

Reading Bram Stoker's Dracula was a disturbing experience that I cannot forget. The story unfolds through journal entries and letters, and centers around a young lawyer who discovers that his client is a vampire. You know that feeling when something is so terrifying and yet so beautiful that you could't look away? That's what Dracula is to me.

It's not the blood and fangs that make this novel so terrifying. It's a mix of horror and sweetness. Dracula is a figure filled with majesty and grotesque elegance. It's not only a monster: it's an enigma, charming yet deadly, poetic yet predatory.

This paradoxical charm, manifested in character and setting, left me torn between fear and fascination. And that, to me, is far more haunting than mere gore or shock factor. This is a book that not only scares, but additionally haunts, remaining in your memory long after you place it down.

Reviewed by Wayne Wong, Lecturer in Asian Studies

The Haunting of Hill House, Shirley Jackson (1959)

Krystyna/Flickr, CC BY

“Hill House is mean, it's sick,” heroine Eleanor Vance muses as she approaches the titular mansion from Shirley Jackson's 1959 novel Haunted Hill House. She is invited as a part of a small group to research a supposed ghost inhabiting the constructing, but her relationship with Hill House quickly becomes obsessive.

The reason it stuck with me greater than every other novel is since it's a book about how we turn out to be convinced of things lurking in dark corners. Jackson, like me, suffered from parasomnias comparable to sleepwalking and nightmares, and there are moments in The Haunting of Hill House where fear manifests itself in Vance's sleep and dream-like trance states.

In my very own book Night terrors, I write about how restless sleep could make you’re feeling such as you're haunted. Jackson's book perfectly shows how our minds create their very own ghosts.

The review was written by Alice Vernon, lecturer in creative writing and nineteenth century literature

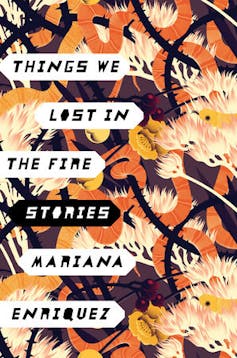

Things We Lost within the Fire – Mariana Enriquez, translated by Megan McDowell (2016)

Penguin, CC BY-SA

A book that also scares me each time I give it some thought Things we lost in the hearth, a 2016 collection of short stories by Argentine author Mariana Enríquez. The stories take conventional horror tropes – murder, mutilation, molestation and the occult – and weave them into contemporary stories about Buenos Aires.

The stories oscillate between satirical realism and brutal surrealism, often if you least expect it. For example, a story about poor tourism turns right into a nightmare wherein the heroine not knows whether the young mother and child she met were murdered or didn’t exist in any respect. Elsewhere, a neighbor concerned concerning the well-being of a toddler experiences a shocking encounter with a monster that completely overturns our assumptions.

In the title story, young women take a stand against widespread mistreatment in a terrifyingly deliberate and systematic purge by fire. Here, the private is each political and terrifying.

The review was written by Carina Hart, assistant professor of applied English

Woman in Black, Susan Hill (1983)

Penguin, CC BY-SA

There is nothing more terrifying than isolation. A spot miles away from the closest house or village where, as cliché because it sounds, nobody will hear you scream. Susan Hill Woman in black is a very shocking example of this. Lawyer Arthur Kipps is hired to sort out the estate of the late Alice Drablow and sets off on a journey to her home, Eel Marsh House.

The home is separated from the closest village by a causeway that disappears at high tide. This leaves Kipps trapped in the home, accompanied only by his dog Spider and the wandering specter of the Woman in Black, who haunts Kipps as he tries to unravel the mystery of the Drablow family.

Professionally written, the novel gently introduces you to horror stories you won't soon forget. No literary moment moved me greater than Hill's painfully slow description of Spider, standing upright and listening as an empty rocking chair scrapes against the nursery floor.

This review was written by Lucy Atkinson, a PhD candidate in Creative Writing

Les Chants de Maldoror – Isidore Ducasse (1868-1869)

New directions

Written under a pseudonym Count Lautreamont, Les Chants de Maldoror (The Songs of Maldoror) by Isidore Ducasse didn’t scare me, but his paintings haunted me for a very long time. This demented and surreal work transports readers into the mind of Maldoror, a misanthropic wanderer who delights in his unrepentant evil.

The book's self-proclaimed “poison pages” have a nightmarish quality, containing disturbing and sometimes darkly poetic descriptions of murder, malice, and madness. These are mixed with images from fever dreams, comparable to Maldoror copulating with a shark – the one predator that’s his equal.

An act of youthful provocation (Ducasse was only 24 when he died a yr after its publication), this book is a literary bayonet into God, society, and the moral taboos that sustain it. Arranged in six “instructive poems,” Ducasse's fantasies of torture, violence, and humiliation powerfully remind us that our own dark, antisocial impulses will be way more disturbing than any supernatural horrors.

The review was written by Karl Bell, a cultural history reader

Are you on the lookout for something good? Cut through the noise with a curated collection of the newest releases, live events and exhibitions straight to your inbox every two weeks on Fridays. Sign here.

Image Source: Pixabay.com