In 1855, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported the gruesome murder of a bride by her recent husband. The story comes from a French countryside where the lady's parents initially prevented the couple from getting engaged “due to the strange behavior sometimes observed in the young man,” regardless that “he was otherwise probably the most elite[g]possible match.”

The parents finally gave their consent and the marriage took place. Shortly after the newlyweds left to finish their bond, “terrifying screams” got here from their quarters. The people quickly arrived and located “the poor girl… in the agony of death – her breast torn and torn in the most terrible manner, and the unfortunate husband in a fit of madness and covered with blood, who had actually devoured part of the unfortunate girl's breast.”

The bride soon died. Her husband also died after “the strongest resistance”.

What could have caused this terrifying event? “Then, in response to the doctor's inquisitive questions,” it was recalled that the groom “had previously been bitten by a strange dog.” The transmission of madness from dog to human appeared to be the one possible explanation for the macabre turn of events.

The Eagle matter-of-factly described the episode as “a sad and disturbing case of hydrophobia” or, in today's parlance, rabies.

But this account reads like a gothic horror story. It was essentially a werewolf narrative: the bite of a rabid dog caused a hideous metamorphosis that transformed its human victim right into a vile monster whose vicious sexual impulses led to obscene and disgusting violence.

My recent book titledMad Dogs and Other New Yorkers: Rabies, Medicine, and Society within the American Metropolis, 1840-1920”, explores the hidden meanings within the ways people discuss rabies. Variants of the story of the offended groom had been told and repeated in English-language newspapers in North America since at the very least the early 18th century, and continued to look until the Nineties.

The Eagle's account was essentially a folk tale about mad dogs and the skinny line between man and beast. Rabies was feared since it was a disease that appeared to turn people into rampaging beasts.

A terrible and fatal disease

Lucas Cranach the Elder, Ducal Museum/Wikimedia Commons

Historian Eugen Weber once noted that French peasants within the nineteenth century were afraid of “mainly wolves, mad dogs and fire” Dog madness – the disease we all know today as rabies – has caused dog fears which were a nightmare for hundreds of years.

Other infectious diseases – including cholera, typhoid fever and diphtheria – he killed many more people within the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The cry of “mad dog!” nevertheless, it created a right away sense of dread, as a straightforward dog bite could mean a protracted ordeal of grueling symptoms followed by certain death.

Modern medicine knows that rabies is attributable to a virus. Once it enters the body, it reaches the brain through the nervous system. The typical interval of weeks or months between initial exposure and the onset of symptoms signifies that rabies isn’t any longer a death sentence if the patient receives treatment promptly injections of immune antibodies and a vaccine to construct immunity soon after encountering a suspicious animal. Although people rarely die from rabies within the United States, the disease still occurs kills tens of hundreds of individuals world wide yearly.

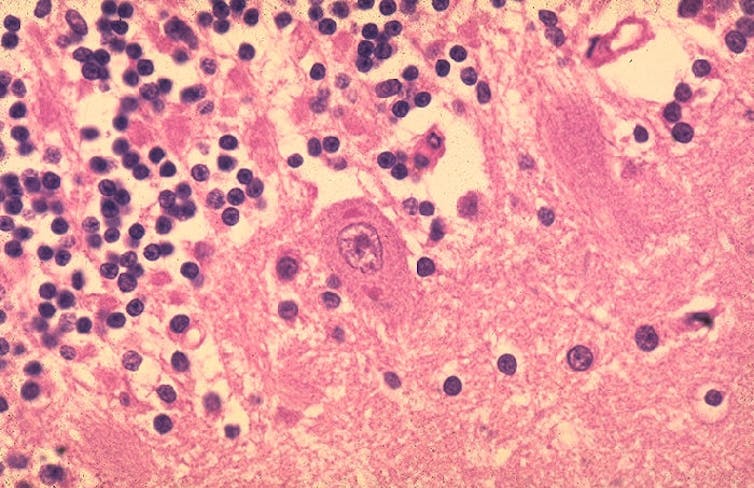

CDC/Dr. Makonnen Fekadu, CC BY

According to nineteenth century sourcesafter an incubation period of 4 to 12 weeks, symptoms may begin with a vague sense of agitation or anxiety. They then progressed to the devastating spasmodic episodes characteristic of rabies, accompanied by insomnia, excitability, fever, rapid pulse, salivation, and labored respiratory. Victims often showed hallucinations or other mental disorders.

Efforts to calm drug flare-ups often failed, and doctors could then do little greater than stand by and bear witness. Final release occurred only when the disease inevitably led to death, often inside two to 4 days. Even today, rabies stays essentially still present incurable once clinical symptoms appear.

Centuries ago, the lack of bodily control and rationality brought on by rabies gave the look of an attack on the victims' basic humanity. From a terrifying animal-borne disease emerged spine-chilling visions of supernatural forces that channeled the ability of malevolent animals and turned humans into monsters.

Bites that turn people into animals

Nineteenth-century American accounts never made direct reference to the supernatural. However, the descriptions of the symptoms indicated unspoken assumptions about how the disease transferred the essence of the biting animal to the suffering human.

Newspapers often described individuals who contracted rabies from dog bites as barking and growling like dogs, while cat bite victims scratched and spat. Hallucinations, respiratory spasms and uncontrollable convulsions created the terrifying impression of the evil mark of a rabid animal.

Traditional preventive measures also showed how Americans have quietly established a blurred line between humanity and animality. Folk remedies held that dog bite victims could protect themselves from rabies by killing the dog that had already bit them, placing the dog's hair on the wound, or cutting off its tail.

Such preventive measures implied the necessity to cut the invisible, supernatural bond between a dangerous animal and its human prey.

Sometimes the disease left uncanny traces. When a Brooklyn man died of rabies in 1886, the New York Herald reported a bizarre phenomenon: inside minutes of the person's last breath, “the bluish ring on his hand – the mark of the Newfoundland's fatal bite… disappeared.” Only death broke the destructive grip of a mad dog.

The roots of vampires in mad dogs

It's possible that alongside werewolves, vampire stories also come from rabies.

Doctor Juan Gómez-Alonso noticed resonance between vampirism and rabies within the hair-raising symptoms of the disease – distorted sounds, exaggerated facial appearances, anxiety, and sometimes wild and aggressive behavior that made victims seem more monstrous than human.

The extreme hypersensitivity to stimuli that triggers the tortuous spasmodic episodes related to rabies can have a very strange effect. Looking right into a mirror can trigger a violent response, a terrifying analogy to a living, dead vampire's inability to reflect back.

Moreover, in various folkloric traditions of Eastern Europe, vampires turned not into bats but into wolves or dogs, the major vectors of rabies.

AP Photo/Daniel Hulshizer

As aspiring werewolves, vampires and other creatures take to the streets this Halloween, do not forget that beneath the annual ritual of candy and costume fun, there lie darker corners of the imagination. Here, animals, diseases and fear mix, and monsters materialize on the intersection of animality and humanity.

Cave Caneme – be careful for the dog.

Image Source: Pixabay.com