In the novel Joe Rogan podcastBritish physicist Brian Cox argued that we have a great responsibility to extend our civilization because it may be the only source of meaning in the cosmos.

However, in the grand scheme of the cosmos, the future existence of humans may not matter for the same reason that the extinction of the dinosaurs did not attract the attention of the cosmos. Humans only appeared on the cosmic scene within the last one percent of cosmic history, and no one from cosmological distances could care less. Other space players may not be interested in making their presence known to us because our earthly bragging rights don't carry much weight in the space dating scene.

Given that there are a hundred billion older habitable planets in the Milky Way alone, it is likely that creatures like us existed on exoplanets in the past. Their electromagnetic signals may have long since disappeared because it takes only tens of thousands of years to travel through the Milky Way at the speed of lightweight, a few millionths of a complete period of cosmic history.

Whether anything remains of dead civilizations depends on the force with which they went into interstellar space. Our own interstellar probes: Voyager 1 and 2, Pioneer 10 and 11, and New Horizons will leave the Solar System's Oort Cloud within twenty thousand years and will then constitute one trillionth of the population of interstellar objects of the same mass. We know very little about space debris from other civilizations because astronomers have only discovered the first interstellar objects in the last decade.

Brian is not looking for scientific evidence about interstellar space probes. His opinions on the possible existence of extraterrestrials are no better informed than those of a layman. The only way for science to make a difference is to seek novel evidence of the existence of extraterrestrials. This is my day job as a practicing astrophysicist.

The Galileo project under my direction aims to collect observational data on anomalous extraterrestrial objects near Earth. It is based on the scientific method of relying on evidence, not prejudice. Apart from analysis materials taken from the site of the first interstellar meteorite in the Pacific, the Project Galileo research team will release novel data next month on the half a million near-Earth objects monitored by a novel observatory at Harvard University.

The crucial question is what we should assume as our default assumption. Brian advocates the conventional choice that we are alone until proven otherwise. This, of course, gives us a sense of self-importance and eliminates the urgent need to invest resources in searching for evidence.

But physicists like Brian don't insist that shadowy matter doesn't exist until it's discovered. Since we have not yet discovered shadowy matter particles, the most conservative view should have assumed that known matter and radiation are the only cosmic ingredients. Instead, physicists have invested billions of dollars in searching for specific types of shadowy matter particles.

The motivation was indirect evidence for the existence of shadowy matter, based on its gravitational influence on the dynamics of evident matter and radiation. Nevertheless, if gravity happens to be modified at diminutive accelerations, this indirect evidence will be misinterpreted.

The existence of habitable Earth-sized planets around other stars is circumstantial evidence that conditions favorable to life may be common. However, mainstream folklore prefers to make the implicit assumption that aliens may not exist. One of the arguments raised by Brian is that if they existed, we would have detected them by now.

As I explained today on the podcast with Deepak Chopra, our own technological features, such as city lights, industrial pollution, and space rockets, are arduous to see against the backdrop of the expansive interstellar space. We must also remember that the search for extraterrestrial technological signatures has been funded by less than one percent of shadowy matter searches. If so, why would we insist that shadowy matter exists and gravity is unmodifiable, while arguing that extraterrestrials might not exist without elaborate space probe attempts to detect them?

Science is exhilarating because it offers the opportunity to search for evidence. Expressing opinions on scientific issues without taking the time and effort to answer them is unscientific.

The greatest advances in our scientific knowledge came as a surprise. This includes the experimental discovery of quantum mechanics a century ago, something no theorist expected. It also covers pioneering theoretical concepts such as Stephen Hawking's statement about black hole evaporation, inspired by Jacob Bekenstein's observations about black hole entropy – which Hawking initiated in an attempt to disprove, and Yacov Zeldovich's observations about vacuum fluctuations – which Hawking learned about during a trip to Moscow.

This latest inspiration was mentioned by Kip Thorne in a public lecture he gave last week at Harvard's Black Hole Initiative, of which I was founding director and where the first images of black holes were obtained.

Stephen Hawking was very interested in the possible existence of extraterrestrials when he visited my house for the launch of the Black Hole Initiative in 2016. Stephen was particularly concerned about the existential risk from alien predators. Here again my opinion differs from the British: aliens probably don't care about us.

Because most stars formed billions of years before the Sun, aliens could have embarked on interstellar travel long before humans separated from nature thanks to newfangled science and technology. We should look for aliens not out of fear, but because their scientific discoveries could provide us with a quantum leap in our scientific knowledge. The inspiration we can draw from advanced alien scientists may be like Hawking's inspiration from Bekenstein and Zeldovich on steroids.

Instead of remaining trapped in an echo chamber that reinforces our prejudices about our privileged cosmic status, it would be wiser to assume that we are typical students in a classroom of clever civilizations. After all, the Copernican principle has proven wiser than the alternative in the past. It offers a more modest default assumption than the idea that we are privileged.

We hope that our observatories will eventually connect us with our cosmic neighbors. Copernicus and Galileo used observational data to ultimately oppose the geocentric model of space and the Vatican he admitted that in 1992 they were right. Today, a novel type of clergy advocates an egocentric model of the cosmos without relying on scientific evidence.

We will all do much better in the long run by having an intriguing approach to space. Science at its best is an educational experience, fueled by curiosity and the humility of admitting that we are not as vital on the space scene as we are led to think.

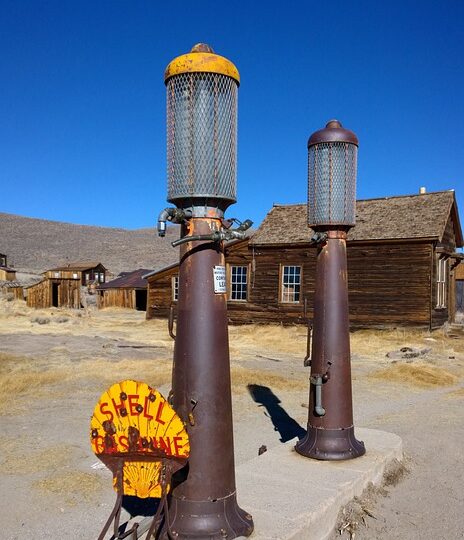

Image Source: Pixabay.com